- Timeless Autonomy

- Posts

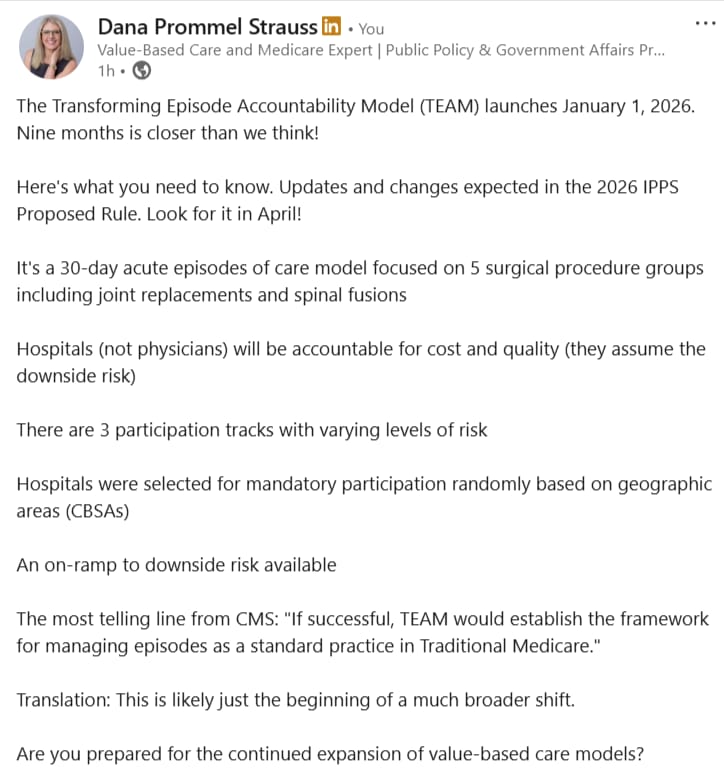

- T-Minus Nine Months Until TEAM

T-Minus Nine Months Until TEAM

I smell denial in the air

TEAM Could Lead to Hospital Care Transformation

Today I want to focus on why I like the TEAM model so much and why I think you should, too. I’m relatively surprised there’s so little chatter about it when there’s so much to put in place to ensure success in the model. There’s plenty of money to lose, never mind what can be left on the table, if ducks aren’t in a row in time. 🦆 🦆 🦆 🦆

Here is a resources dashboard on the TEAM Model. See the Final Rule page with important parts of the 2025 IPPS Final Rule broken out into small components. Make sure you check out whether or not your hospital is in the model!

Here are Timeless Autonomy articles on TEAM from last year, labeled by the order in which I recommend reading them:

What I love most about TEAM is that it holds acute care hospitals accountable for their ability or failure to improve upon what they can control and that impacts the short, mid, and long-term success of patients. It’s not what a particular surgeon is going to do or not do that will improve outcomes. Good surgical technique is just table stakes.

But it’s the multidisciplinary care team itself that will have the largest part to play in the long-term outcomes for surgical patients. Good surgical technique is not just table stakes, it’s incentivized. Doing everything in a hospital’s power to ensure that the episode of care journey the patient takes is the one that’s the best for them,?

That’s not directly incentivized.

It was so important that CMS got that part right. Hospitals at risk in this circumstance, not physicians.

What I love second most is that all hospitals in the chosen CBSAs are included. Do you know why? I won’t give it away now, but reply back if you want to guess!

Not everyone will agree with my positive sentiments about TEAM. But let me try to convince you I’m right, anyway. 😁

Why I’m confident TEAM’s structure is good and the model is important and will help transform acute care so it’s better for patients—

There’s a lot that’s done, and a lot that’s not done, in acute care hospitals under the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System’s incentive structure. Yes, hospitals vary, but like all businesses, they are at least incentivized to be in regulatory compliance and to do what will improve their financial health and the success of the organization.

Let me tell you a little about how hospitals are paid (overly simplified, but it’s sufficient for this exercise)—

Hospitals are paid for inpatient stays in Medicare by coding for one primary “Diagnostic Related Group” or “DRG,” that’s finalized shortly after the patient’s hospital stay. Certified Coders are responsible for this and they follow guidelines.

This part is important to understand:

It doesn’t matter if a patient is admitted for the expected/average length of stay for the DRG or a different length of stay. The DRG payment “is what it is.” If you wonder why hospitals want to discharge patients quickly, it’s because they lose money if patients stay longer than “expected.” And they essentially “earn” more if their stay is shorter than “expected.”

The DRG covers the vast majority of care in the hospital. Surgical and Intensive Care DRGs are some of the highest paying DRGs as a whole. That makes sense, because more resources are used to provide their care.

DRGs do not cover the cost of physicians’ services, including surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc. But they do cover all other professional services such as PTs, OTs, STs, dieticians, etc. that bill via the physician fee schedule when provided in an outpatient setting. Unfortunately, this makes these services de facto “cost centers.” And that has had negative material impacts on at least the therapy professionals and how they are viewed by the healthcare delivery system, policymakers, and by physicians, in my opinion. But I digress…

Physicians bill under Medicare Part B in the hospital for their Medicare Fee-for-Service/Traditional Medicare patients. Their reimbursement is fully separate from that of the hospital. Of course, hospitalists and others employed by the hospital are paid by the hospital, but the billing is to Medicare Part B. Every physician or nurse practitioner or physician assistant or clinical nurse specialist or nurse anesthetist that sees you in the hospital bills (or their employer bills) for that care.

So with that in mind, knowing there’s essentially one payment to cover all the services provided in the hospital other than physician services, here’s is a little more of what a hospital is incentivized and not directly incentivized to do for the success of their business 👇️

They are incentivized to attract and retain good surgeons and intensivists, to discharge patients promptly, to prevent poor publicly-reported and quality metrics, to have high patient satisfaction scores, etc.

Here are some things they are not incentivized to do. That doesn’t mean some hospitals do these things anyway, but that’s not what they are directly incentivized or required to do:

Make sure patients maintain as much strength and mobility as possible during their inpatient hospital stay. Develop and maintain robust mobility programs and have strict structures in place to ensure everyone without a present (those on bedrest re-evaluated at least every shift) contradiction to mobility is mobilized optimally.

Do everything possible to make sure patients who can go home, go right home instead of an inpatient post-acute site of care (with follow-up appointments, home health or in-home outpatient therapy or other options and communication between inpatient and outpatient providers as handoffs).

Ensure all physician consults provided during the hospital stay are medically necessary.

Make sure patients who need more therapy get more, and those who need less therapy get less. Mobility is for nearly everyone. Therapy is a consultative professional service that should be referred when medically necessary. It should not routinely be a consult made because a patient lost significant strength due to avoidable bedrest. That bedrest shouldn’t be happening in the first place.

Ensure all clinical staff understand what the experience of post-acute settings are like for patients, what they can expect, and what the post-acute teams can and can’t change, and the difference between custodial care and skilled care. They make sure they understand what the true Medicare guidelines are for home health, skilled nursing facilities, inpatient rehab facilities, and long-term acute care hospitals.

Here’s something I used to hear from hospital rehab departments that was a universal problem when trying to improve on discharging more patients home. I would invariably here them say “patient unsafe, discharge to SNF.”

The thing is, being “unsafe” is not a justification for discharging to a SNF. They may have not been safe before. That won’t change by going to a SNF. Think the SNF will do something to “make them safe?” No, generally they won’t.

And “not being safe” is not a reason Medicare covers the stay in a SNF. The Medicare guidelines for SNF are called the “Chapter 8 Guidelines.” There is nothing in the guidelines that has anything to do with whether a patient is “safe.”

(Start on page 18 of the Chapter 8 Guidelines pdf to read this section: Care in a SNF is covered if all of the following four factors are met if…)

If they are in a hospital and don’t have the adequate amount of “custodial” support AND don’t NEED DAILY skilled care, they need to go home with a plan to have more support and receive intermittent skilled care with home health. It’s the job of the acute care hospital to solve for the inadequate support problem.

Another way to think about this is the SNF will have the exact same problem when planning discharge. What often then happens is the patient makes a little progress, then it stalls because the person is in a wheelchair almost all the time. They don’t need daily skilled care. But the SNF doesn’t have a plan to discharge them home so they just keep them and keep billing Medicare day after day.

Sometimes a SNF will exhaust the person’s SNF benefit. They will keep them for 100 days and then discharge them home if they won’t pay privately to stay. And while they are still unsafe to go home, they send them home anyway, and this time, they have no SNF Medicare benefit left, either.

Yes, this actually happens.

So I have coached therapists to think about the rehab prognosis and functional prognosis after getting a strong understanding of their day to day function over the prior few months and the year leading up to the hospital admission. And then using that information and their evaluation of the patient during the stay, what’s realistic for this patient in terms of function? Is this an issue of needing more support, a different living situation, or of training someone that is already present? Or is there something specific that ONLY daily skilled therapy in a SNF can change that will impact the patient’s trajectory of care?

The answer to that determines whether or not the patient’s right next level of care is SNF or a lower level of care.

And a story for another day, but an inpatient rehab facility’s (IRF) admission criteria is different. Patients are candidates when something significant about their function changed rapidly (injury, trauma, medical event, specific surgeries). They should be able to tolerate 3 hours per day of therapy and make significant progress. IRF is NOT the place for someone with progressive deconditioning or a typical medical illness.

Require certain standardized, best practice protocols are followed (aside from individual exceptions) for all surgeries agnostic of which surgeon and anesthesiologist are involved.

Ensure the patient-related best choices are made based not on the cost of a product or service, but what will most likely lead to the best short and long-term outcome. (I share an example of this in our upcoming podcast episode.)

Educate patients and families about post-acute settings, what to expect, and what a setting of care can and cannot do. Ensure all clinicians understand the same.

Do warm hand-offs between a hospital provider and a provider in a post-acute setting or outpatient setting.

Do warm hand-offs between a rehabilitation professional team member in acute care and a rehabilitation professional at the next site of care.

Ensure patients and families understand their individual rehab prognosis (Example on the upcoming pod!).

You are probably asking why that all matters

In the TEAM model, the hospital is responsible for or rewarded for spend that is above or below the expected cost of the hospital stay PLUS thirty days after.

Let’s break it down in a overly-simplified example using fictional reimbursement amounts associated with each service provided during the episode.

The TEAM Model predicts the expected cost of the total knee replacement surgery plus all other costs billed in the 30 day period starting the day of discharge is $25,000 in Mrs. Smith, an 80 year old female in northeast Pennsylvania.

The DRG payment for Mrs. Smith is $15,000. The surgeon fees are $2500. The anesthesiologist fees are $2000. All other physicians’ charges combined are $1500. Then Mrs. Smith went to SNF A for 12 days for $8000. Then they had a home health episode of care for $1500 and the 30 days is done.

That’s $31,500. Everyone was paid like they normally would be paid. That’s more than was expected by the model for Mrs. Smith.

Then the hospital owes $6500 back to CMS.

If the patient had an ER visit during the episode or had an infection requiring treatment, or any other event, those costs would add even more to the “owe” column. Because of unexpected events, all episodes that can have an ideal patient journey should have an ideal patient journey. Success (don’t owe money to CMS and hopefully earn money from performance that was better than expected) or “failure” is in aggregate across all episodes.

Now, we have to do better.

No, we can’t control everything. But we can control far more than we have been previously-incentivized to in fee-for-service hospital care.

Here’s some of what I would want to know if I was looking for the opportunities in Mrs. Smith’s case:

Why did she go to a SNF after a TKR rather than home health, home with outpatient PT, or right to outpatient PT?

Did the surgeon and team establish a discharge to home plan before the surgery?

Was the best anesthesia block option provided to optimize pain relief while minimizing impact on muscular control and shortening the time to first mobilization?

What prevented her from discharging to home?

What prevented a shorter length of stay in the SNF? (SNFs are reimbursed on a per diem basis, not like a hospital is paid. For many patients with a TKR, on or around 7 days is ideal.)

TEAM is more complicated than this, obviously. But if you understand this much, you understand more than the vast majority of healthcare professionals!

Pro tip: Let the incentives be your guide. If you want to figure out why something is being done a certain way or not being done a certain way, look at the payment incentives. It’s usually a shortcut to the solution.

Here’s a “short” from a recent episode. Just keep in mind this is a work in progress 🙂 : 👇️

And if you didn’t know I have a podcast, which I co-host with the awesome Alex Bendersky, subscribe to receive updates from us and the episodes right to your inbox. Plus, you receive free resources curated by us, updated with each episode, and a link to access the resources when you subscribe.